Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline Photos

Bloomed out fireweed along the James Dalton Highway, commonly called the Haul Road, Trans Alaska oil pipeline, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

The Alaska oil pipeline extends 800 miles from the north coast of the Arctic Ocean south to the coastal waters of Prince William Sound in Valdez. It traverses tundra, rivers, streams, and rugged mountain passes, standing the test of time as a true engineering feat. I have hundreds of trans-Alaska oil pipeline photos covering the diverse terrain it passes. All the trans-Alaska oil pipeline photos on this site are available for licensing as stock photos for commercial use or purchase as fine art display prints for your home and office decor. Images may be purchased and downloaded through this website by clicking on the pictures or following the gallery links.

Pipe array in the Prudhoe Bay oil field, Arctic Coastal Plain, Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Pipeline and Wildlife

The pipeline was purposely raised high off the ground to span rivers or allow wildlife to cross beneath the pipe.

A grizzly bear walks across the tundra in the Prudhoe Bay oil fields on Alaska’s Arctic North Slope. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Barren ground caribou, Rangifer tarandus, migrate across the tundra north of the Brooks Range, Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Cow moose near Wiseman, Alaska, along the Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

The trans-Alaska oil pipeline traverses the tundra landscape of Interior Alaska, south of Delta Junction. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Northern lights over the Tanana River and the suspension bridge for the Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline in Delta Junction. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Trans Alaska oil pipeline crosses the Little Miller Creek in the Alaska Range mountains, Interior, Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

About The Oil Pipeline

Oil was discovered at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, in 1968 after explorers had searched since the 1950s through Northern Alaska. A pipeline was considered the only viable system for transporting the oil to the nearest ice-free port, almost 800 miles (1,300 km) away at Valdez. Completed in 1977, the Alaska pipeline covers 800 miles of mountain, muskeg, and river valleys from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. Stretch the channel over the Lower 48, reaching from Los Angeles to Denver.

Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline traverses the tundra of Alaska’s Arctic, north of the Brooks mountain range. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

The Pipe

The pipe is a tube of 1/2-inch thick steel with a diameter of 48 inches. It looks more comprehensive from the highway because the steel pipe is wrapped with four inches of fiberglass insulation. The shiny wrapping we see is a coat of aluminum sheet metal. The closer oil is to the earth’s molten core, the hotter it is when oil companies pull it to the surface.

Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline, Fairbanks, Alaska (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Oil Temperatures

Oil pumped from the Prudhoe Bay field, which is 10,000-to-20,000 feet deep, is about 145 to 180 degrees Fahrenheit. Using heat exchangers that work like a car’s radiator, the oil is cooled to about 120 degrees before it enters the pipeline. The temperature within the pipeline is relatively constant despite variations in ambient temperatures along the line. The temperatures can range from nearly 100 above to 80 below Fahrenheit, the Alaska record cold temperature set on January 23, 1971, at Prospect Creek Camp on the Dalton Highway. The four inches of fiberglass insulation surrounding the above-ground pipeline keeps the oil warm enough to flow even on the coldest winter days. If the pipeline had to be shut down in the winter, the oil within could sit for several months before congealing.

Trans Alaska Oil pipeline traverses the snowy tundra of the arctic north slope of Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Permafrost

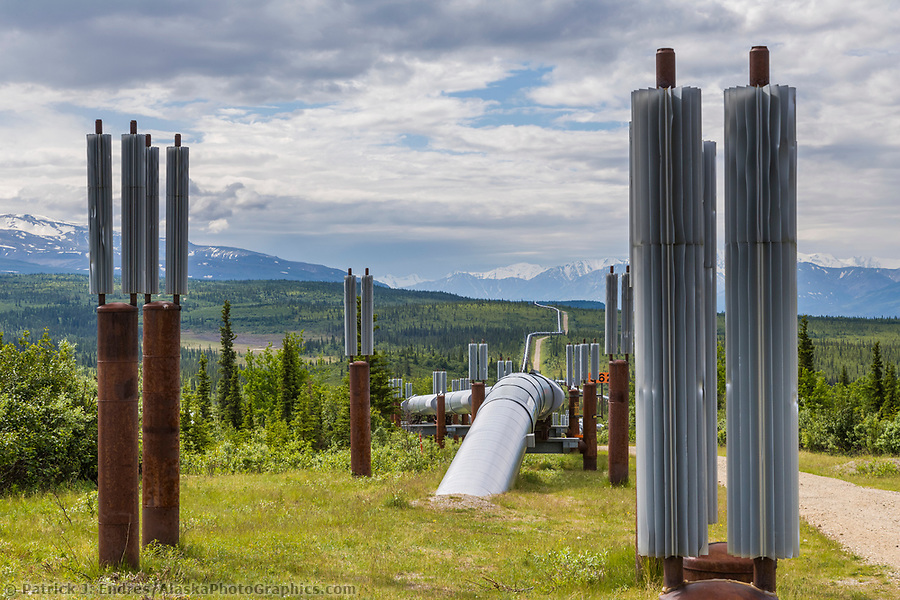

Engineers would have buried the entire pipeline had it not been for permafrost (permanently frozen soil) lying in sheets and wedges beneath the surface. The pipeline couldn’t be buried in permafrost because the heat of the oil would cause the frozen ground to melt. The pipe would then sag and possibly leak. Because much of Alaska is underlain with permafrost, Alyeska routed just over half the pipeline above ground. Where it snakes over land, the pipeline is supported by posts designed to keep permafrost frozen. Topped with fan-like aluminum radiators, the posts radiate heat from the ground into the cold winter air to keep the soil solidly frozen. When the air temperature is 40 below, the bars cool down to 40 below and remove heat from the soil, ensuring the ground stays frozen.

Trans Alaska oil pipeline is buried whenever possible, but permafrost soil conditions require the pipeline to be above ground. Metal fins help dissipate heat and cold. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline in Atigun canyon, Brooks Range, Alaska (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

The Shape of the Pipeline

The pipeline was built in a zigzag pattern to allow the pipe to expand and contract. Because workers welded much of the pipeline at temperatures well below zero, engineers anticipated that the metal would expand once-hot oil began flowing through. The zigzag also allows the pipeline to flex during earthquakes; it slides over H-shaped supports with Teflon-coated “shoes” on the crossbar between the posts holding up the pipeline. Where the pipeline crosses seismic faults–weak areas of rock that rupture during earthquakes when the plates of the earth grind against one another–it sits on rails. Near the Denali Fault south of Delta Junction, the pipeline rests on 20-foot steel bars that allow it to move side-to-side should an earthquake cause the earth’s crust to slip laterally along a fault line.

The zigzagging Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline parallels the James Dalton Highway, Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Trans Alaska oil pipeline on slide rails as part of the earthquake-resistant engineering. Alaska Range mountains, Interior, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Alyeska workers do service maintenance on the Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline in Atigun canyon, Brooks Range, Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Oil Travel

Powered by the heartbeat of 10 pump stations, oil flows through the pipeline at about the speed of the Yukon River, carrying a raft about 5 to 7 miles per hour. At that rate, it takes about five-and-one-half days for oil to complete the journey from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. Once the oil reaches the terminus in Valdez, it is loaded onto tankers and transported through Prince William Sound.

Vehicles travel along the Richardson Highway, Trans Alaska oil pipeline pump station in the distance. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

On March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez grounded on Bligh Reef in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, rupturing its hull and spilling nearly 11 million gallons of Prudhoe Bay crude oil into the pristine waters of the Sound. By volume, the Exxon Valdez oil spill is the second largest in US waters after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon. Prince William Sound’s remote location made response efforts difficult. Whipped up by a wind storm, the oil spread widely, ravaging the ocean life, and its toxicity killed many ocean organisms, birds, marine mammals, and wildlife. The oil eventually covered 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of coastline and 11,000 square miles (28,000 km2) of the ocean.

The Polar Enterprise oil tanker travels north into the Valdez Arm, Chugach mountains range, and borders the Prince William Sound, Alaska channel. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

This article is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community & the aid of Alyeska Pipeline Service Company’s Elden Johnson. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.