Polar Bear photos

Polar bear cubs play fight on a snow-covered island in the Beaufort Sea, Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus)

The polar bear, or Nanook in the Inupiat language of Alaska’s Arctic indigenous peoples, is truly the lord of the Arctic. It has adapted to survival in one of the most severe environments on earth. Watching and photographing this animal walking along an arctic shore, then directly into a frigid ocean, and swimming amidst chunks of ice is nothing less than mystifying. The polar bear photos on this site are predominantly of the southern Beaufort Sea population along Alaska’s far northeast Arctic Coast. All images may be licensed as stock photos for business use or purchased as fine art prints for your home or office decor.

Polar bear on an iceberg in the Beaufort Sea, off the coast of Barter Island, Kaktovik, Alaska (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

General description

Polar bears are whitish to ivory in color, with large feet and a long and slender neck designed for efficient swimming. They have an acute sense of smell which they use to hunt and find seals on the open ice pack. They are typically solitary animals living alone on the ice pack but can tolerate community gatherings when significant food is present. The Polar bears are related to the brown bear as they share a common ancestor. Adult males average 600 to 1,200 pounds (273-545 kg) but may reach 1,500 pounds (680 kg). They average between 8 and 10 feet (2.4-3.0 m) in length. Mature females weigh 400 to 700 pounds (182-318 kg). Bears typically live about 25 years.

Polar bear on the Beaufort Sea Ice in Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Arctic Adaptations

a white coat with water-repellent guard hairs and dense underfur

short furred snout

short ears

teeth specialized for a carnivorous rather than an omnivorous diet

and hair nearly completely covering the bottom of the feet.

Polar bear on the Beaufort Sea Ice in Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Polar bear swimming in the Beaufort Sea, Arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Mating

Male polar bears begin seeking out females in late March through May by following their tracks on the sea ice. Bears are polygamous; the male remains with a receptive female for a relatively short time and then seeks another female. Females can produce a litter every third year.

Denning

Pregnant females begin denning on land and the sea ice in late October and November. She excavates a depression in the snow under a bank, on a slope, or near rough ice and enlarges the den as drifting snow accumulates. A litter of two cubs is the most common, born in December.

Polar bear sow and cub sit at the water’s edge on a barrier island in the Beaufort Sea, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Cubs

The female and cubs emerge from the den in late March or early April when cubs weigh about 15 pounds (6.8 kg). They make short trips to and from the open hole for several days as the cubs become acclimated to outside temperatures. They then start traveling on the drifting sea ice. Cubs most commonly remain with the mother until they are about 28 months old.

Polar bears on sea ice in the Beaufort Sea, Romanzof mountains of the Brooks Range in the distance. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Distribution

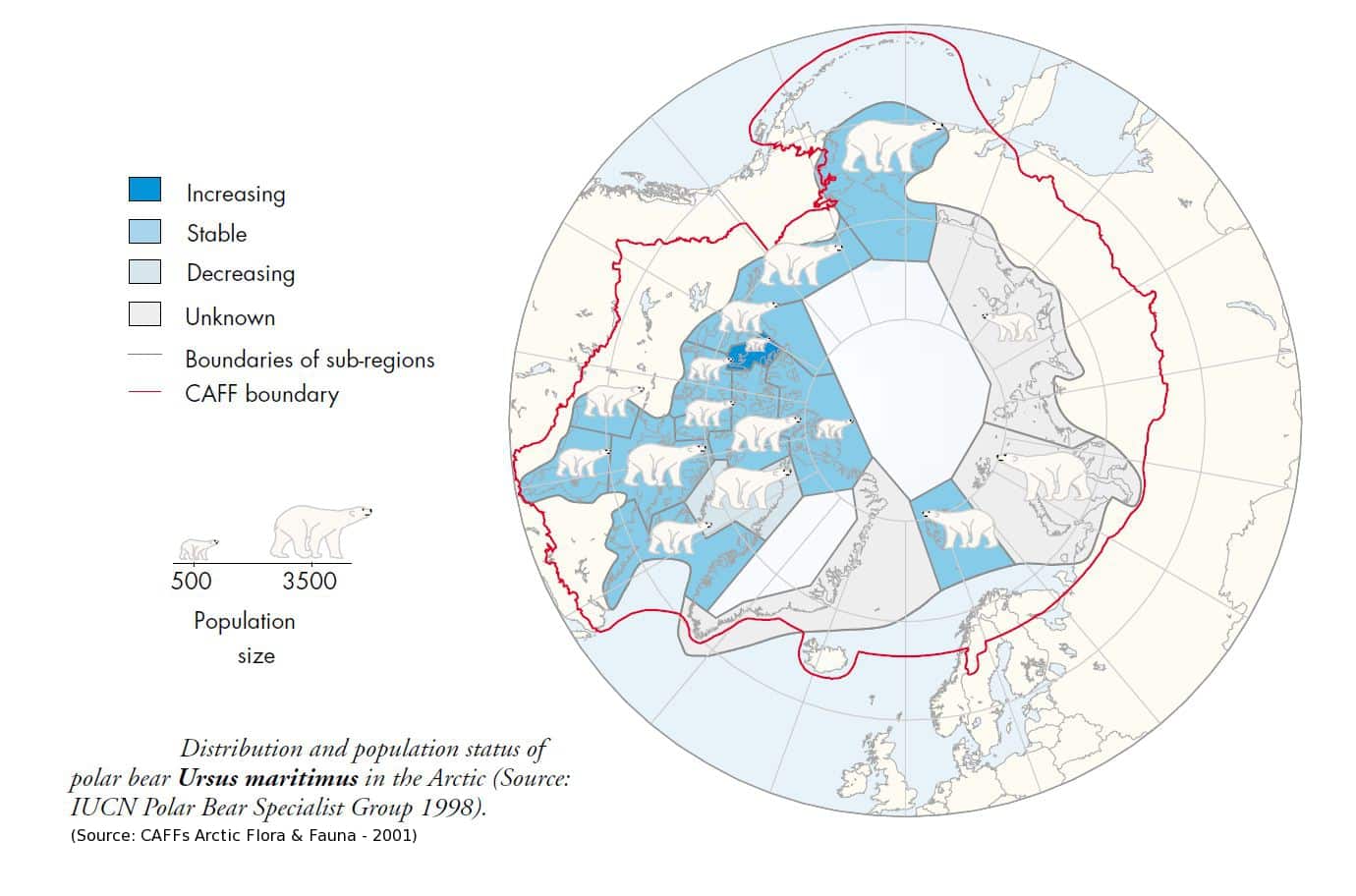

Polar bears are most abundant near coastlines and the southern ice edge, but they can occur throughout the polar basin. They make extensive movements related to the seasonal position of the ice edge. In winter, bears off Alaska commonly occur as far south as St. Lawrence Island and may even reach St. Matthew Island and the Kuskokwim Delta. During the summer, bears occur near the edge of the pack ice in the Chukchi Sea and the Arctic Ocean, mostly between 70° and 72° north latitude. Some denning occurs along the north Alaska coast, especially within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and on the adjacent sea ice. Off Alaska’s coast, there are two polar bear populations.

The Beaufort Sea population (which is the predominant source for the polar bear photos in this article) occurs along the North Slope of Alaska and ranges into western Canada.

The Chukchi population occurs off western Alaska, with its range extending to Wrangel Island and eastern Siberia.

Polar bear population distribution. Arctic Portal Library.

An adult female polar bear walks along the snow-covered shore of an island in the Beaufort Sea on Alaska’s Arctic coast. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Food

The leading food of the Alaska population is the ringed seal. Bears capture seals by waiting for them at breathing holes and at the edge of leads or cracks in the ice. They also stalk resting seals and catch young seals by breaking into pupping chambers. A keen sense of smell, sharp claws, robust strength and speed, and the camouflaging white coat aid them in hunting.

Bears prey to a lesser extent on:

Bearded seals

Walruses, and beluga whales

Carrion: including whale, walrus, and seal carcasses they find along the coast

Occasionally small mammals, bird eggs, and vegetation when other food is not available.

On Alaska’s north coast, polar bears gather in late summer to feed on the carcasses of Bowhead whales discarded by the Inupiat villages. The indigenous communities hunt whales under management by the World Eskimo Whaling Commission.

Polar bears feed on a Bowhead whale carcass on Barter Island, Alaska. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Polar bears on the newly formed sea ice on the Beaufort Sea along Alaska’s Arctic Coast. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Human Uses

In Alaska, before the late 1940s, nearly all polar bear hunting was by Eskimos with dog teams. Hunting, sometimes with aircraft use, started in the late 1940s and continued through 1972, when Alaska prohibited aircraft use. With the passage of the Statehood Act, Alaska began a polar bear management program. State regulations required sealing of skins, provided a preference for subsistence hunters, and protected cubs and females with cubs.

Polar bear in the village of Kaktovik, Barter Island, Arctic, Alaska (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Native Alaska Inupiaq subsistence hunting remnants in Utqiagvik (Barrow), Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Hunting and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA)

The MMPA of 1972 transferred management authority from the state to the federal government and placed a moratorium on hunting marine mammals by people other than Alaska Natives. This resulted in a reduced total harvest but an increased proportion of female bears and cubs. The MMPA includes provisions that allow for waiver of the moratorium or transfer of management authority back to states. At intervals since 1972, the state of Alaska has made efforts at regaining polar bear management. State management could allow a resumption of sport hunting and produce increased economic opportunities in coastal rural communities. For various reasons, efforts to regain state management have been discontinued.

Polar Bear Conservation

Representatives of the five polar bear nations prepared an international agreement on the conservation of polar bears in November 1973. The pact was ratified in 1976. It allows bears to be taken only in areas where they have been taken by traditional means in the past and prohibits the use of aircraft and large motorized vessels as an aid to taking. The agreement has created a high seas polar bear sanctuary but does not prohibit recreational hunting from the ground using traditional methods. In Canada, the recreational hunting of polar bears currently provides significant economic benefits to Native people.

A female polar bear rubs her neck in the snow on an island in the Beaufort Sea on Alaska’s Arctic coast. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Polar bear cub rolls in the falling snow on an island in the Beaufort sea, arctic, Alaska. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Habitat and Climate Change

The degradation of polar bear habitat is currently of more concern than the effects of hunting on populations. Human activities, especially those associated with oil and gas exploration and extraction, pose the greatest immediate threat. Oil exploration and drilling activities in denning areas could cause bears to den in less suitable locations. Oil spills from offshore drilling and transportation of oil through ice-covered waters could contaminate bears and reduce the insulating value of their fur or adversely affect animals in the food chain below them. Severe environmental conditions would hinder or prevent the containment of a spill, and currents and ice movement could distribute oil over large areas.

A polar bear covers its face with its giant paws while rolling in the snow on an island in the Beaufort Sea on Alaska’s Arctic coast. (Patrick J. Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Photographing Polar Bears in Alaska

Polar bears have become a popular subject for wildlife photographers. They are as amazing to watch as they are fun to photograph. Alaska’s Arctic coast along the Beaufort sea offers some unique photo opportunities. The Arctic Village of Kaktovik has developed a small industry in polar bear tourism. The bears congregate near the village to feed on bowhead whale carcasses while they wait for the sea ice to form. During this time, residents of Kaktovik offer tour access to the bears via small boats where photography can occur from a safe distance.

A photographer takes a picture of a polar bear from a boat along Alaska’s Arctic coast. (Patrick J Endres / AlaskaPhotoGraphics.com)

Some text adapted from the Alaska Fish & Game Wildlife Notebook Series.